The Renaissance

Few historical concepts have such powerful resonance as the Renaissance. Usually used to describe the rediscovery of classical Roman and Greek culture in the late 1300s and 1400s and the great pan-European flowering in art, architecture, literature, science, music, philosophy and politics that this inspired, it has been interpreted as the epoch that made the modern world truly modern. But the term ‘renaissance’ (French for ‘rebirth’) was never used during the period itself – it was invented by 19th-century historians – and its remit is still hotly disputed. Did the Renaissance begin in late 14th-century Italy, during what’s usually regarded as the Middle Ages, or only flower in northern Europe a century later, in the aftermath of the Protestant Christian Reformation? Does it describe a cultural, historical and economic moment, or a gradual process – and, if so, when did it end? Did man really ‘re-find him’, as one French historian later wrote? Or does the word describe something much subtler and more indefinable?

Rebirth and rediscovery

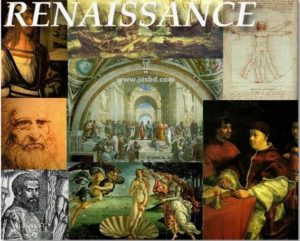

Though historians debate the precise origins of the Renaissance, most agree that it – or one version of it – began in Italy sometime in the late 1300s, with the decline in influence of Roman Catholic Christian doctrine and the reawakening of interest in Greek and Latin texts by philosophers such as Aristotle, Cicero and Seneca, historians including Plutarch and poets such as Ovid and Virgil. One spur was the fall of Constantinople (Istanbul) to the Turks in 1453, which encouraged many scholars to flee to Italy, bringing printed books and manuscripts with them. The extraordinary flowering in visual art that occurred in the great Italian city states of Florence and Venice in the early 16th century, including artists such as Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael, was another. Yet another was Johann Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press around 1440, which enabled books to be mass-produced in the Western world for the first time. Aided by a quickly shifting political landscape, and an increase in trade and economic activity, these new ways of thinking began to spread northwards across Europe. The fact that it was a transnational movement, which came to touch every country in Europe, is one of the most crucial things about the Renaissance.

Humanism

As already suggested, education was a driving force, encouraged by the increase in the number of universities and schools – another movement that began in Italy. Gradually, the concept of a ‘humanistic’ curriculum began to solidify: focussing not on Christian theological texts, which had been pored over in medieval seats of learning, but on classical ‘humanities’ subjects such as philosophy, history, drama and poetry. Schoolboys – few girls were permitted to receive an education at this point – were drilled in Latin and Greek, meaning that texts from the ancient world could be studied in the original languages. Printed textbooks and primers enabled students to memorise snippets from quotable authors, sharpen their use of argumentative rhetoric and develop an elegant writing style – one textbook by the Dutch humanist educator Desiderius Erasmus from 1512 famously includes several hundred ways to say ‘thank you for your letter’.

In Britain, humanism was spread by a rapid increase in the number of ‘grammar’ schools (as their name indicates, language was their primary focus, and students were often required to speak in Latin during school hours), and the jump in the number of children exposed to the best classical learning. Shakespeare, Marlowe, Spenser, Jonson, Bacon: almost every major British Renaissance intellectual one can name received a humanist education. Shakespeare’s plays and poems are steeped in writers he encountered at school – the magical transformations of Ovid’s poetry infiltrate the worlds of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest, his Roman histories are cribbed from the Greek historian Plutarch, The Comedy of Errors is modelled closely on a Greek drama by Plautus, while Hamlet includes an entire section – the Player’s account of the death of Priam – borrowed from Virgil’s Aeneid.

The Reformation

But humanism produced a strange paradox: European society was still overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, yet the writers and thinkers now in vogue came from classical, pre-Christian times. The clash was made more obvious in 1517, when a renegade German friar called Martin Luther, appalled by corruption in the Church, launched a protest movement against Catholic teachings. Luther argued that the Church had too much power and needed to be reformed, and promoted a theology that stressed a more direct relationship between believers and God.

Another central plank of his thinking was that the Bible should be available not just in Latin, spoken by the elite, but democratically available in local languages. Luther published a German translation of the Bible in 1534, which – assisted by the growth of the printing press – helped bring about translations into English, French and other languages. In turn, this increased literacy rates, meaning that more people had access to education and new thinking. But the political consequences for Europe were violent, as war raged and Protestant and Catholic nations and citizens vied for control.

New worlds

As much as the rediscovery of old culture was important, it’s impossible to understand the European Renaissance without referring to the way in which its horizons increased – both scientifically and geographically. In 1492, the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus landed in the Bahamas while seeking a westwardpassage to Asia, initiating a headlong rush by European powers for resources and territory in this so-called ‘New World’. Throughout the 16th century, maritime powers such as Spain, Portugal and – later – England battled for control of what became America and the West Indies, while adventurers and traders also pushed eastwards, around Africa, towards East Asia. Money was the driving force (there were fortunes to be made in minerals, spices, cloth and other goods, not to mention the slave trade), but so was political and religious ideology, with colonial expansion presented as a Christian crusade to bring enlightenment to ‘uncivilised’ populations. While the cost for indigenous people was vast – it is still being counted – Europe profited enormously from these encounters, with new wealth flowing into major population centres and exotic goods such as silk, spices and ceramics available for the first time.

Geographical discoveries mirrored scientific ones. The Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) posited that the Earth moved around the Sun, not the other way around, as had been assumed for centuries – a theory proved through close observation by the Italian polymath Galileo Galilei (1564–1642), who also refined the mechanical clock. The magnetic compass (first used by Chinese sailors in the 11th century) was belatedly rediscovered in early 14th-century Italy, revolutionising navigation. The use of another Chinese invention, gunpowder, also spread across Europe, with a dramatic and brutal effect on warfare. And – yet again – the printing press helped in incalculable ways, spreading ideas faster and faster.

How did the Renaissance affect culture?

The Renaissance affected culture in innumerable ways. In painting, sculpture and architecture, Italian artists such as Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael experimented with naturalism and perspective, and pushed visual form to more expressive heights than had ever been witnessed. Writers such as Boccaccio, Petrarch and Montaigne used insights gleaned from Latin and Greek texts to develop literature that had the polish and elegance of classical authors, yet was more intensely personal than ever before. Composers including Palestrina, Lassus, Victoria and Gabrieli experimented with interweaving polyphony and richly coloured harmonies, far more formally complex than their medieval antecedents. Political thinkers such as Machiavelli honed a statecraft based on realpolitik, while thinkers such as Galileo and Francis Bacon stressed the importance of science based on real-world experiment and observation. The fact that so many of these people were polymaths – skilled in music as well as art, writing as well as science – is itself testament to Renaissance attitudes to life and learning.

An English Renaissance

Although the Renaissance arrived in England in the mid-1500s, almost two centuries after it began in Italy, some of its greatest achievements occurred on these shores, particularly in literature. Courtier-poets such as Sir Thomas Wyatt, Sir Philip Sidney and Edmund Spenser transformed Italian forms into richly flexible English verse, while composers including Thomas Tallis, William Byrd and Orlando Gibbons learned from the harmonic experiments being conducted in mainland Europe to forge a harmonic language uniquely their own.

Perhaps most strikingly, playwrights such as William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson put their grammar-school educations to fine effect in the public theatres of London by creating drama more sophisticated and psychologically powerful than anything else in Europe. Marlowe’s anti-hero Tamburlaine, a snarlingly ambitious shepherd from a central Eurasian backwater who rises to be an all-powerful ruler, is one kind of Renaissance man. Shakespeare’s Hamlet – a conscience-racked Danish revenger who is educated in the Lutheran town of Wittenberg, and who delivers existential philosophy worthy of Montaigne – is another. The word ‘renaissance’ may be tricky to define, but the impression it left on culture is impossible to mistake